Conflict exists in every organization and to a certain extent indicates a healthy exchange of ideas and creativity. However, counter-productive conflict can result in employee dissatisfaction, reduced productivity, poor service to clients, absenteeism, increased employee turnover, increased work-related stress or – worst case scenario – litigation based on claims of harassment or a hostile work environment.

In this section, we look at managing the day-to-day conflict that occurs in all workplaces – ways to identify and understand it and ways to manage it effectively. As an executive director or manager, it is often your role to discern when a conflict is a normal part of the work day and work relationships, or whether you need to engage an external alternative and/or refer to a more formal conflict resolution policy and procedure.

HR Management Standard 4.5

The organization has established procedures and informed employees with regard to how to resolve conflicts within the organization.

Conflict is an inevitable part of human relationships. Where commitment to mission and long hours with minimal resources intersect, workplaces can be rife with conflict interchanges. Conflict can arise from managing differing perspectives and seemingly incompatible concerns. If we can accept it as a natural part of our emotional landscape, it can be easier to work with than if we expect (or wish!) conflict to disappear and never resurface.

As a manager, it is important to be able to identify and to understand the varying levels of conflicts and how these levels are manifested in different ways. An early sign of conflict is that "nagging feeling" or tension you feel, indicating that something is brewing under the surface. Pay attention to non-verbal behaviours such as crossed-arms, eyes lowered or someone sitting back or away from you or the group. These signs can provide you with important information about your current situation and can help you assess your next steps. If these signs are not dealt with in a timely manner, this sense of apprehension can shift to another level of conflict and can be manifested more directly with opposition and conviction. This aspect of conflict is addressed in more depth in the sections below.

More often than not, these early warning signs are a part of a larger web of dynamics present in your organization. As part of the analysis, it is helpful to understand the source of potential conflict. Below are some common sources of conflict:

Conflict type |

Description |

Values conflict |

Involves incompatibility of preferences, principles and practices that people believe in such as religion, ethics or politics. |

Power conflict |

Occurs when each party wishes to maintain or maximize the amount of influence that it exerts in the relationship and the social setting, such as in a decision-making process. |

Economic conflict |

Involves competing to attain scarce resources, such as monetary or human resources. |

Interpersonal conflict |

Occurs when two people or more have incompatible needs, goals or approaches in their relationship, such as different communication or work styles. |

Organizational conflict |

Involves inequalities in the organizational chart and how employees report to one another. |

Environmental conflict |

Involves external pressures outside of the organization, such as a recession, a changing government or a high employment rate. |

Once you know more about where the conflict stems from, you will be better equipped to address it. A variety of factors influence when and how conflict will surface. To get the bigger picture, consider all the sources above before taking action. Now, we will look at the various ways in which we can respond and manage conflict.

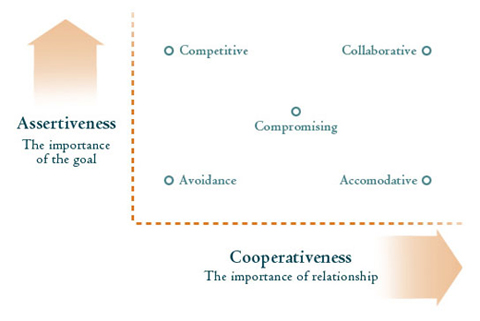

Thomas and Kilman (1972) developed a model that identified five common strategies or styles for dealing with conflict. They state that individuals tend to have a personal and habitual way of dealing with conflict which can take over when we are under pressure. Sometimes it's the most productive style for resolving the conflict, but very often it's not and simply worsens the situation. A first step in dealing with conflict is to discover your preferred conflict style(s) and subsequently, learn how to manage a variety of situations using different approaches.

These styles have two basic dimensions:

Assertiveness, which relates to behaviours intended to satisfy one's own concerns. This dimension is also correlated to attaining one's goals,

Cooperativeness, which relates to behaviours intended to satisfy the other individual's concerns. This dimension can also be tracked as being concerned with relationships.

Each style is appropriate in particular contexts, and learning how to be strategic when approaching conflict is ideal.

The accommodating style is unassertive and cooperative. The goal of this stance is to yield. Typically a person using this conflict mode neglects her or his needs to satisfy the concerns of the other person. There is an element of self-sacrifice and this stance is concerned with preserving the relationship versus attaining goals. The mode is also known as an appeasement or smoothing style and is the opposite of competing.

Example:

Catch phrase: "It's ok with me. Whatever you want."

Pro: Can preserve harmonious relationships, can admit there is a better way

Con: Can lead to resentment by not getting your needs met, can diminish your influence, and be a martyr stance

The Competing style is a power-oriented mode that is high in assertiveness and low in cooperation. The goal of this stance is to win. In this mode, the individual aims to pursue her or his agenda at another's expense. This may mean standing up for one's needs, defending a cherished position and/or simply trying to win. The goal is deemed very important. This style is also referred to as a forcing or dominant style.

Example:

Catch phrase: "My way or the highway."

Pro: Decisive, assertive, addresses personal needs

Con: Can damage relationships, shut others down

The avoiding style is both unassertive and uncooperative. The goal of this stance is to delay. In this mode, an individual does not immediately pursue her or his concerns, or those of another. There is indifference to the outcome to the issue and the relationship, and the person withdraws or postpones dealing with the conflict. This style can provide a needed respite from the situation or it can inflame things if the issue keeps being pushed aside. This mode is also known as flight.

Example:

Catch phrase: "I will think about it tomorrow."

Pro: Doesn't sweat the small stuff, delays may be useful

Con: Avoidance builds up and then blows, important issues don’t get dealt with, it can take more energy to avoid than deal with issues directly at times

The collaborating style is both assertive and cooperative. The goal of this stance is to find a win-win situation. Typically this mode is concerned with finding creative solutions to issues that satisfy both individual's concerns. Learning, listening and attending to both the organizational and personal issues are addressed with this conflict style. It takes time and effort. This mode is also known as a problem solving or integrative style. It is the opposite of avoiding.

Example:

Catch phrase: "Two heads are better than one."

Pro: Finds the best solution for everyone, which leads to high commitment, higher creativity in problem solving, team-building

Con: Takes time and energy; if applied to all conflicts it can be draining and unnecessary

The compromising style lands one right in the middle of being assertive and cooperative. The goal of this stance is to find a quick middle ground. Parties find an expedient, mutually acceptable solution by having each person give up something and split the difference. This mode is also known as sharing.

Example:

Catch phrase: "Let's make a deal."

Pro: Fixes things quickly, satisfies needs of both parties, finds temporary settlements to complex issues, has back-up strategy when competition or collaboration fails

Con: Can play games, bypass longer-term solutions, compromises found may be dissatisfying and may need to be revisited

Read more on conflict resolution.

While every person can use all five conflict styles at different times, we tend to prefer one or two habitual responses in conflict situations. For example, a person may unconsciously use the compromising style of approaching conflict even when the situation would move more quickly and effectively using an accommodating approach. In order to be effective in conflict situation, you will need to learn to expand your use of conflict strategies.

An easy way to use the conflict styles strategically is to use the following grid. First, assess your situation: What is the most important to you? Team? Organization? Is it the goal or is it the relationship involved? When the relationship matters the most, use the strategies on the right of the grid (i.e., collaboration or accommodation). If it is vital to maintain the goal is above all else, you could use the top two strategies of the grid (i.e., competitive or collaborative). When the result and relationship are both relatively important to you, a compromising style will probably be most effective. If neither the goal nor relationship matter, avoiding conflict may be the best bet.

Cheat sheet:

goal high (most important) and relationship low = compete

goal low and relationship high = accommodate

goal AND relationship high = collaborate

goal AND relationship low = avoid

goal and relationship are equally important = compromise

The grid is useful for thinking through any given situation.

ECEC Example:

An executive director and program manager are trying to finalize the details of a letter. The output or goal, an excellent letter that conveys the right message, is of great importance to both of them and in fact the entire organization. Having a dynamic and harmonious relationship between the executive director and the manager will ensure a long working relationship. Both parties are known for their individual expertise in their respective areas and are needed to sign off on this letter. As tensions rise, collaboration (creative problem solving) would be the most beneficial as long as both parties were willing to take the time to find a win-win situation. By harnessing their goodwill and skill, they may come up with a better option that far surpasses what either party suggested in the first place. In this case, both the working relationship and the goal are of primary importance.

When working in a group, there may be times when you will have to work with a difficult person. Often, this person is not aware of her or his impact on the group, or the implications of her or his actions on others. Depending on the perspective, everyone has been viewed at one time or another as a difficult person. Everybody has the capacity to be both productive and problematic in the workplace. It is all in how you view the situation. With a simple change in perspective, your experience with a difficult person can change from a situation that is happening to you to a possibly enriching learning experience.

If you are experiencing a strong reaction to another person, there are two elements you need to consider: you and the other person. First, start with yourself. It is essential to understand why you are reacting to that person and the possible strategies you can use to address the situation. For example, a preferred conflict style can be exacerbated by a particular method of communication. If you have a tendency to avoid conflicts, are e-mails the only way you solve issues at the office? Or do you find yourself saying things on e-mail that you would never say in person. Many of us can hide behind our computers or take on a bolder, more aggressive persona. In essence, change your behaviour to work effectively with someone. There are many ways in which to communicate with your colleagues – for example, face-to-face meetings, phone calls, e-mails, video conferencing. The possibilities are limitless.

When working with a difficult person, begin to locate the problem inside yourself. Dr. Ronald Short, in his book, Learning in Relationship, states: "The impact someone has on us (feeling and thoughts we have inside) is our responsibility. To understand impact, we need to look at ourselves – not judge others" (1998). Remember, as a rule (and this is easier said than done), try not to take things personally. Nothing others do is because of you. What others say and do is a direct reflection of what is happening inside of this person.

Once you have a clearer idea why this person is upsetting you and have a broader perspective on to why she or he might be acting a certain way, you are in a good position to engage in a conversation.

Important: Remember, you can only control your response to the conflict, not the outcome. Sometimes people are just difficult and nothing you can do will change this reality. More often than not, there are other forces at play in someone else's behaviour that are beyond our capacity to deal with. Although it is important to understand this fact, it doesn't lessen the negative impact and emotional turmoil a difficult person can have on you and your organization. While dealing with difficult people may be an unavoidable fact, in no way is bullying ever acceptable.

If you decide to address the person involved, remember that successful conflict resolution depends on effective communication. This, in turn, depends on two factors: (1) acknowledging, listening, and productively using the differences in people; and (2) developing a personal approach for dealing effectively with difficult people.

When this type of discussion is conducted successfully, it results in far more than a simple change in how you address the situation or your use of language. Remain open and curious: you have so much to learn from each other. Conflict strategies, however, are one side of the coin; how you handle communication in relation to conflict is the corresponding side. Check out the section on interpersonal communication to get some ideas on how to communicate effectively.

Links and Resources

Recognizing Workplace Aggression in the Non-Profit Sector: Taking Action

The Community Health Promotion Network Atlantic (CHPNA) created this important handbook for nonprofit organizations in response to concerns over aggression in the workplace.Managing Workplace Conflict

This site was developed by the Vancouver Island University in British Columbia to help its employees deal with conflict in the workplace. The university offers a unique perspective on how to approach an employee, manage anger and handle criticism.

Some reading

The Director's Toolbox, by Paula Jorde Bloom and Kay Albrect, is a series of five books published by New Horizons.

A Great Place to Work, by Paula Jorde Bloom, published by the National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC).

Working Through Conflict: Strategies for Relationships, Groups, and Organizations (5 ed.), by Joseph P. Folger (2004), provides an introduction to conflict management that is firmly grounded in current theory and research.

Learning in Relationship: Foundation for Personal & Professional Success by Dr. Ronald Short (1998), provides a series of short thinking lessons which help the reader locate the source of the communication problem not within the other person, but inside oneself.

Newsletter Signup

Follow Us